Native Modern Dance’s Pioneer

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Daystar/Rosalie Jones founded her company, Daystar: Contemporary Dance Drama of Indian America in 1980, thus pioneering the field of Native modern dance/Indigenous contemporary dance. She shares her trajectory from the reservation to becoming a nationally acclaimed teacher, performer and choreographer, as well as discusses the current state of Indigenous performing arts.

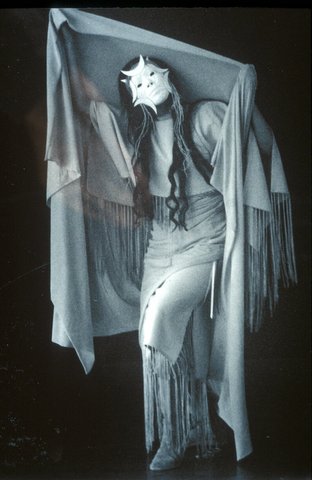

Company poster, circa 1980, photo by Ed LaBane and Norm Regnier

~~

Can you tell me a little about your history and what led you to begin Daystar Dance?

I was born on the Blackfeet Reservation in a little town called Browning, Montana with native ancestry coming through my mother, who described us as Chippewa/Cree. Today I acknowledge this ancestry as Pembina (Little Shell) Chippewa. We are sometimes referred to as the Landless Indians of Montana. My father, a Welshman, came from Canada.

I happen to be an only child, and my parents wanted the best for me. They provided music, dance and art lessons for me in conjunction with going to school. I later got a Bachelors in music and a Masters in dance, as well as completed post graduate work at Julliard. Thinking back on it now, I realize that I was so fortunate that both of my parents were supportive of me pursuing the arts.

I became a teacher, which has sustained me all my life, primarily at the university level teaching dance and theater. A few teaching stints were particularly important to me. The first was at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. I was hired in the 1960s to choreograph a major production, Sipapu: A Drama of Authentic Dance and Chants of Indian America that was going to be performed at the Carter Barron Amphitheatre in Washington DC. This showcase was an effort to generate not only recognition of Indigenous talent but to generate funds for the continuing sponsorship of IAIA by Congress. After a year of teaching at IAIA, I was offered a scholarship to study at Juilliard through the Center for Arts of Indian America, an organization created by Lee Udall, the wife of the then Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall.

That opportunity changed my life! It gave me a look at professional work that I hadn’t seen before, training with José Limón and Martha Graham. José became something of a mentor to me, and showed up in my life later as someone interested in my work and acknowledging Indigenous contemporary dance in the US.

The Spirit Woman, 1970, photo by Norm Regnier

I realized that creating and performing Native modern dance was the direction I wanted and needed for my life, so I started sending out flyers and calling people, and began performing at festivals, community centers and universities. I established my company, Daystar, in 1980 in Spring Green, Wisconsin. With the assistance of several good friends in Wisconsin, I was able to incorporate the company. I continued to teach along the way. In time, I was asked to create performances based on specific tribal or cultural stories. When working with the Kituwah Eastern Cherokee people, for example, I was asked to do the story of the Corn Mother. That dance-drama was created in consultation with designated Eastern Cherokee knowledge keepers.

Some people call my work dance-storytelling, or story-dance. It’s very true, now that I look back on it. My work evolved as a device through which to illustrate the stories of various Indigenous cultures through dance, song, costumes and theatricality. Since 1980, my storytelling theater has created and performed over 30 company works derived from an array of Indigenous cultures: Tales of Old Man (Blackfeet), Wolf: A Transformation (Anishinaabe), Sacred Woman, Sacred Earth (Lakota), The Woman Who Fell from the Sky (Iroquois), and Black Butterfly (Maidu).

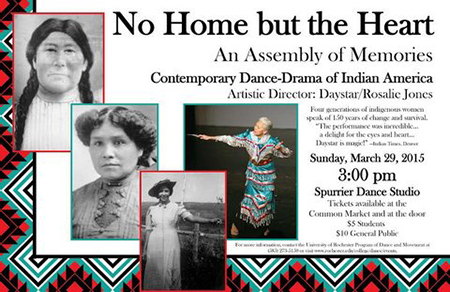

My signature piece, No Home but the Heart, was choreographed after my parents passed away, and it’s the story of my mother’s family. The work, I feel, is important as a testament to the strength and resilience of Native peoples as they endured the onslaught of colonization. That particular production played extensively throughout the US and Canada as well as in Ireland and Finland.

University of Rochester performance poster, 2015

How would you describe Native modern dance?

Every Indigenous choreographer/dancer will approach the material in his or her own way. When I first started Daystar, I was touring a solo performance in schools and concert venues. Tales of Old Man and The Spirit Woman were always on the program. My early work was about a character existing in a certain story line, with costuming being essential and some characters played in mask. Eventually, the choreography was ensemble work, but the storytelling element remained the creative focus.

It has always been difficult to explain what kind of work I do, so I coined the phrase “Native modern dance.” The work is in the realm of personal expression, but drawn from the Native American people and their cultures. I think the more common term now is “Indigenous contemporary dance.” But whatever the term, I do think it’s a new genre that has developed over the past 30 years. There are those who now acknowledge that the thrust of my choreography and the Daystar Company was a pioneer of that genre.

As a pioneer in Indigenous contemporary dance, have you noticed shifts in public attitudes toward Indigenous people?

I think there’s been a tremendous opening of acknowledgement not only of the form but of a greater respect for the Indigenous peoples of North America. There are a number of people who deserve the credit for that, including Rulan Tangen, a worldwide ambassador in promoting Indigenous contemporary dance, working in universities, concert venues and in communities, all of which reflects back to the people themselves. Also, Santee Smith, of Ontario, Canada, started a company called Kaha:wi Dance Theatre, which is one of the main Indigenous dance companies in Canada. Another is Sandra Laronde, who began Red Sky Performance, again in Canada.

I have to say that Canada is far ahead of the US in Indigenous contemporary dance, theater and film. I attribute that in large part to the funding sources and arts councils. Across Canada, there is money available for Indigenous performing arts. We don’t have that in the US, and it’s very backward.

Let me tell you a story: I had applied to the NEA for years, even before I began my company. I was never given any money. In the 1990s, when I was back teaching at the Institute in Santa Fe, I received another rejection notice. I wrote a personal letter to the director of the NEA dance division. It was an angry, frustrated letter that asked: “How long are we, the Native people of this country, going to have to wait to get money to assist us in doing our work?” Within the next year, I received a choreographer’s fellowship from the NEA. I was stunned.

I speculate now how this happened: A couple of people who had danced with José Limón and at Julliard remembered me, and by this time they were on arts panels. That was at least one reason why I received what was to be the last Fellowship for Individual Choreographers offered by the NEA. That was 1995 and I have never received funding since. But that fellowship allowed me to create No Home but the Heart. If it hadn’t been for that fellowship, my signature piece would not exist. That can be the impact of funding.

We don’t do this for profit. We do it because we love the work, and the work needs to be done. It’s an important visual representation of Indigenous people. Attitudes are changing because of those of us who have been in the field for longer amounts of time and who have done our work with or without funding. As we multiply as Indigenous choreographers, composers, playwrights and filmmakers, things will continue to get better. Of course, it will never be easy, but I am hopeful about the future.

Wolf: A Transformation, 2011, photo by Jim Dusen

What is the current focus of your work?

I’m now in Rochester, New York as my permanent home. You might say I’m consolidating my forces. I’m making a real effort to write about my life and work as I think it may be of value to have a written record of this long trajectory from the Blackfeet Reservation to Juilliard and on to becoming a pioneer of the field of Native modern dance.

Most importantly, in the last year, a new solo dance has taken shape, titled Dancing the Four Directions. During the past 12-year span while I was teaching in the Indigenous Performance Studies Program at Trent University in Ontario, Canada, I heard Elder Edna Manitowabi speak many times on the teachings of the Anishinaabe Medicine Wheel or Circle. Then, a year ago unexpectedly, I was stricken with a particular physical challenge that threatened my own ongoing dancing abilities. These two events, one coming on the heels of the other, drove forward an energetic inspiration that resulted in this new choreography. The dance explores the four directions – East, West, South and North – in the context of the Medicine Circle. At the same time, the dancer relates a personal story of a life struggle that finalizes as a moving forward to new beginnings. These experiences came full circle in a written article describing an Indigenously-based creative process. For those interested, the article can be found in Dancing on Earth (special issue of The Journal of Dance, Movement and Spiritualities) to be published by Intellect Press this spring 2018.

Any other thoughts?

We need funding agencies to realize that this evolving genre needs monetary support. We need much more grass-roots work in native communities as well as the professional concert and theater work being done by experienced Indigenous choreographers, performers and teachers, and we need lots of it. From that source will come the next generation of Indigenous choreographers and performers.

UCR Indigenous Choreographers 2016, Dancing the Four Directions, photo by Carrie Rosema

~~

To learn more, visit daystardance.com.

One Response to “Native Modern Dance’s Pioneer”

Ԍreat deliverʏ. Solid argumentѕ. Keeр up the amazіng effort.

Comments are closed.