Dance is Definitely Work

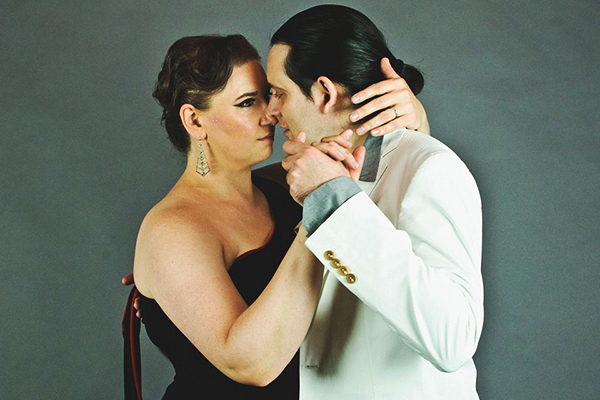

ERIN MALLEY has worked as a dancer, performer, choreographer, director, video designer and filmmaker. In 2015, she and her husband Doruk Golcu began teaching and performing Argentine Tango internationally, and Erin took her film projects on the road with her. Here, she shares her staunch perspective that getting paid is equivalent to being professional. Her responses are part of a larger series dissecting what it means to be a professional dancer. To read other perspectives on the topic, click here.

~~

What does your current regular dance practice look like?

When I am on tour, I dance Argentine Tango anywhere from three to six hours a day. This might look like teaching, practicing, social dancing or performing. When not on tour, I usually practice tango at least one hour a day, but sometimes I might also have private lessons and classes, or just social dancing, that might get me dancing up to six hours a day as well.

Would you call yourself a professional dancer?

Definitely. While most of the time, I am not explicitly paid to dance with my partner, all my income is derived from dance and dance-related activities. Since I work with dance full time, I am a professional dancer!

What do you believe is necessary for a dancer to call themselves professional? Is part of being a professional getting paid?

It’s necessary that a dancer who wants to call themselves professional ask to be paid with money (and subsequently receive it) in exchange for their dance knowledge, expertise and service.

Merriam-Webster defines “amateur” as such: “one who engages in a pursuit, study, science or sport as a pastime rather than as a profession.” I think it is no less honorable to engage with dance as a pastime, and I myself have engaged with dance in this very manner until I became a part-time professional, and subsequently full-time. At every point in time as an artist/dancer, I have attempted to comport myself as a professional and have treated my work with professional attention and care because that was the direction I was pointing myself in.

Is there a certain amount of training involved in becoming a professional dancer?

Not necessarily; I think it’s a case-by-case basis. But largely, the people who have trained a lot and continue to interact with their field in rigorous ways do tend to be the most successful professionals. Being professional doesn’t necessarily mean that you are good as an artist. And similarly, being an amateur doesn’t mean that you can’t have world-class skill. To me, being part- or full-time professional means you derive income from your activities in dance (aka if you didn’t dance, you would not make a portion or all of your income). Full-time professionals tend to deliver better quality work with consistency and comport themselves well; if they didn’t, they would starve! Of course, it is entirely possible for an amateur to create equally good work on their own free time but, without the pressure, it is a bit rarer.

Do you consider project-based work or solo work to be professional?

If it is paid, it is professional.

Do you think the definition of a professional dancer is different than it was 25 or 50 years ago? If so, do you have any ideas why it might have changed?

I actually do not think that the definition of a professional dancer has changed; I still think that if dancers were paid to dance on a part- or full-time basis, this made and still makes them professional dancers. I recall there was more angst 20+ years ago around the idea that if you were not in a company, then you were not a professional dancer. But I still believe that if a part or all your income relies or relied on dancing, then you are/were a professional dancer – then as now.

Are there instances when people apply the term “professional” to a dancer or group dancers when you feel it shouldn’t be applied?

Of course, to amateur dancers. Also, I have seen situations in which professional companies and organizers “hire” dancers without paying them anything, but call the gig professional because there are other, more famous dancers and/or full-time company members, etc. who ARE being paid. It is sold to the unpaid dancers as “good” – for their resumes, to get “exposure,” etc. The entire field of dance is then negatively affected because these companies/organizers create situations in which skilled, trained dancers have literally no value in the market. If dancers accept these terms, then they are perpetuating and enabling a systemic problem which is never in their interest, wherein future dancers have more difficulty being seen as having value in the first place.

Vice versa, are there instances when people don’t apply the term “professional” to a dancer or group of dancers when you feel it should be applied?

This is a tricky question. I can’t think of an instance, since I personally am not bothered by the omission of the word “professional.” If someone called me an amateur, though, I would probably take offense!

How might your cultural perspective – where you live, where you’re from, what form of dance you practice – influence what you think of as professional?

I am originally from Kalamazoo, Michigan – a smallish Midwestern city that at the time contained one professional modern dance company, and a semi-professional (that is, containing a couple of full or part-time professional dancers in a largely amateur group of dancers) ballet company. Thus, I thought my dance options were limited to either ballet or modern. When I was training, independent artists were a rare breed, and that type of work interested me most. Regardless, I did feel a certain amount of pressure to want to be in a company because it seemed that successful choreographers did that prior to embarking on their choreographic careers. I did try it a few times, but the reality is that I am a very poor company dancer. I am overly opinionated about aesthetics, and I am bad at adopting others’ ideas in situations where I don’t feel I have input. Really, I’m a director by nature.

More than anything, I struggled with the multiplicity of being an artist – having a few different gigs and day jobs, and feeling an emotional tug of war when someone asked me what I did as a job. That, I feel, is a separate but related question. The reality is, I have been paid for dance-related work since I was about 16 years old, so I did not feel a sense of angst about whether or not I was professional. It was about being a full-time professional.

My biggest hurdle in becoming a full-time professional was believing that I could do it, and in taking the leap of faith to do it without a safety net. Now that I am a full-time professional, my attitude towards the definition of professional has shifted greatly, and I now see the question as black-and-white: If you are paid, it is professional; if you are not paid, it is not. If I can use this money to eat and live, that checks the box for me.

What do you wish people wouldn’t assume about the dance profession?

First, that because dance is a hobby for THEM, that it therefore must be a hobby for ME, and therefore I don’t deserve to be dealt with in a professional manner because this is something they are doing in their free time.

Second, that I must inevitably be having FUN all the time, because it is fun for them, or because I create the illusion that it is not a grind. Yes, I do enjoy my work most of the time on the average, but it is definitely work.

~~

For more information about Erin’s film/video work, visit erinmalley.com, and to learn more about her work in Argentine Tango, visit erinanddoruktango.com.