Beyond Experimental Dance: An Interview with Paul Langland

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

When I first moved to Santa Fe and started attending the local weekly contact improvisation jam, one of my favorite drop-ins was Paul Langland. Unassuming and easy-going, Paul was always a nice energy in the room. After several months of seeing Paul at the jam here and there, I was blown away to learn he worked with Steve Paxton back in the 70s when contact improvisation was first being developed, and also performed in Meredith Monk’s seminal work. He currently teaches at NYU in the Tisch School of the Arts Experimental Theater Wing, and splits his time between New York and Santa Fe. Before he headed back east for the winter, I seized the opportunity to grab coffee with Paul and learn more about his perspectives on dance.

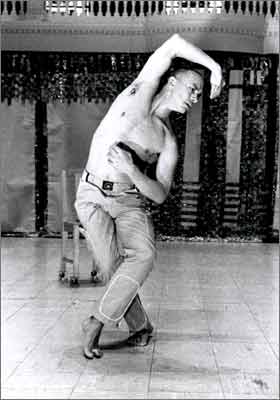

Photo by Michael Popp

~~

How do you explain to someone what kind of dance you do, or what experimental dance is?

It’s very hard to understand, because dance is not a big commercial enterprise except in a very few venues. When I was much younger and said I do contemporary work, people thought it was like Pilobolus. Now they think it’s like Cirque du Soleil. People know about the large acts, and they’re just trying to understand where experimental dance fits into the cultural conversation. Nowadays I say the best way to describe it is one of the directions modern dance has taken.

You can actually look at a lineage that’s very classical. I studied with Steve Paxton, who was in Merce Cunningham’s company. Merce Cunningham was in Martha Graham’s company. Martha Graham was in Ruth St. Denis’ company. Anna Pavlova was hugely influenced by Isadora Duncan and knew about Ruth St. Denis. In a certain way, it’s absolutely logical to trace experimental dance from classical to where we are today. If you’re a serious professional in the dance world, you’re aware of what’s happening in ballet or what the Judson choreographers are up to.

I understand you didn’t train in classical dance. What are your thoughts about classical training, or the negation thereof, in more experimental dance forms?

My very subjective reaction is its nonsense. People should not be limited by a certain ideology or set of values. We’re all adventurers, and no one should deny the use of any technique in making interesting work. We’re in a very eclectic time, and there are some benefits to that: your work can look like anything. Of course you want to find ways in which it has virtuosity and can connect with an audience, but it reminds me of a talk Steve Paxton did about a year ago at St. Mark’s Church in New York. Some people in the contact improvisation world really aren’t interested in dance history or ballet technique, which is fine and their complete right, but Steve comes from an extremely well trained background in modern dance and gymnastics. He basically said he’s not interested in putting up walls between artists. It’s not as if we’re looking at a spectrum of valuable dance techniques and on one side are the red states of ballet and on the other side are the blue states of the contact improvisation world. That’s such a false setup. Let’s celebrate it all. We all need each other.

In thinking about the work you were involved in during the 70s, when you look back on it now, do you have different reactions toward it than when it was happening?

I am, at my core, a culture watcher. In the 70s, even though the Judson choreographers were just starting to become known for their work, I knew it was big. I could feel the shift happening. What’s remarkable to me is how many of my teachers, choreographers and colleagues have exploded into international fame. I didn’t foresee that.

The work they were doing was smart and good, and much of it is really holding up over time. Now it’s almost classic. These pieces have been performed over and over again, and they’re still incredibly beautiful, profoundly human and well-crafted pieces of art.

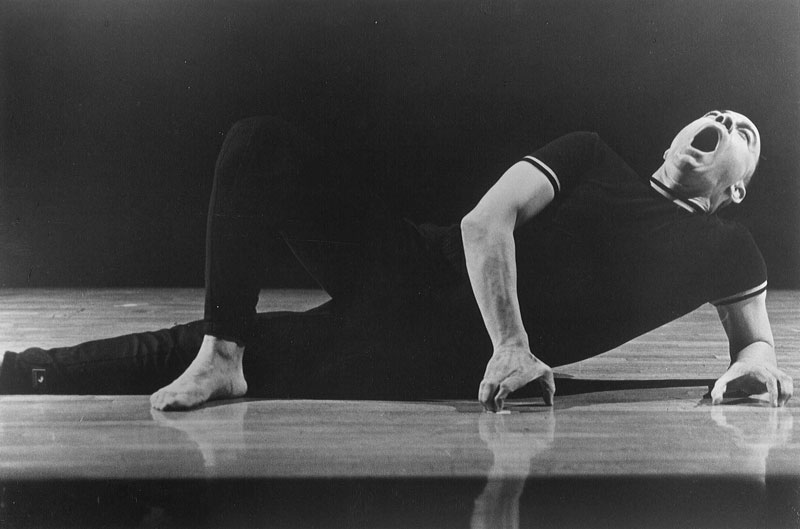

Photo by Anja Hizenberger

I’m curious about the New York dance paradigm. Since you split your time between Santa Fe and New York, do you believe New York is still the epicenter of dance in this country?

Yes, and I think it always will be, partly because of all the hugely important art institutions. It’s a cross roads for international art, from Europe to Asia. There’s a huge mix of dancers in New York at any given moment. The problem is it’s getting increasingly expensive, and dance requires large studios. It’s a conundrum that you’re making work on a budget of $5,000 but you require a million dollar space to work in. That’s what a studio in New York is worth on the open market. Who pays for it? How are entry level dancers supposed to work a job at $20 an hour and come up with $3,000 a month rent? It’s very difficult. You can see that artists have discovered different neighborhoods of New York in an effort to lower their living costs and professional costs. Soho was a dump when I moved there. Then it was the lower east side. Now those are some of the most expensive neighborhoods in the city. Then it was Williamsburg in Brooklyn in the 80s. Now Williamsburg is incredibly chic and expensive. Where in the city can an adventurous young artist gain any momentum?

Since art is a gentrifying force and cities like New York and San Francisco repeatedly push artists out, do you think there’s a movement toward smaller towns?

For many years, a lot of my colleagues were moving to Europe. There’s a tremendous amount of work in Europe, and many people live there or tour there. It’s not something to be taken lightly to leave New York though; on any given night you can go to 20 dance performances.

I come back and forth between Santa Fe and New York because my husband is a visual painter and prefers the fine art scene in Santa Fe. It’s nice to get out of New York, and I appreciate the energy of Santa Fe. In general, there’s a more developed visual arts and music scene, and a less developed theater and dance scene. But for a city of under a 100,000 people, it’s unbelievable. It’s one of a kind.

In smaller places, what you need is an individual to start something. For instance, the University of Oklahoma has a great ballet program because a great ballet teacher moved there and gradually built its reputation. Also, Minneapolis, which has a rather large dance scene, was given a boost by Mary Wigman’s student, Nancy Hauser. One thing leads to the next, people start venues, art agencies grow, but oftentimes it all starts with one person.

You seem to have a really generous perspective toward young people. Sometimes it feels like there’s a sentiment that everything is going downhill. What are your feelings about the future of dance?

I think there will always be adventurers in excellence and new manifestations coming out of the younger generation. Mind you, when I was in my 20s and getting involved in exciting work, I had a lot to learn. I was a little full of myself. I was not from a classical dance tradition; I had a degree in art. I needed to become aware that if I was doing a certain exploration, maybe 50 people had done it already 15 years ago. That’s something that’s good for young people to know. Know your history and know when you’re being derivative. Know when you’re finding something authentic.

At the same time, you can’t worry about that too much. Otherwise you’ll get paralyzed and not make anything. Go ahead and be influenced. If it’s exciting to you, put your own stamp on a style of work you find deeply influential. There’s nothing wrong with that.

Ideas in the dance world travel very slowly because it’s a handmade profession. Dance is hard to commodify. That’s a good thing and a bad thing.

Photo by Tom Brazil

~~

Paul Langland is a choreographer, dancer and teacher who, for the last 42 years, has been an innovator in dance and performance. Paul has been a contact improviser since its discovery in 1972 and was a member of the ground-breaking improvisation ensemble, Channel Z (1983-1987). He was a member of the original Meredith Monk Vocal Ensemble (1974-1985), performing with them again in July, 2000 at Lincoln Center, and in April, 2004 at Town Hall, New York. He performed in such Meredith Monk works as the TRAVELOGUE SERIES (co-choreographed by Ping Chong), QUARRY, SPECIMAN DAYS, RECENT RUINS, ELLIS ISLAND (movie), DOLMEN MUSIC and TURTLE DREAMS. In New York, P.S. 122, Dance Theatre Workshop (now NYLA), The Kitchen, The Franklin Furnace and many other venues have presented Paul’s works. He has also performed and taught at The American Dance Festival and The American College Dance Festival. He is currently an arts professor at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts Experimental Theater Wing.