When Ballet and Contact Improvisation Meet

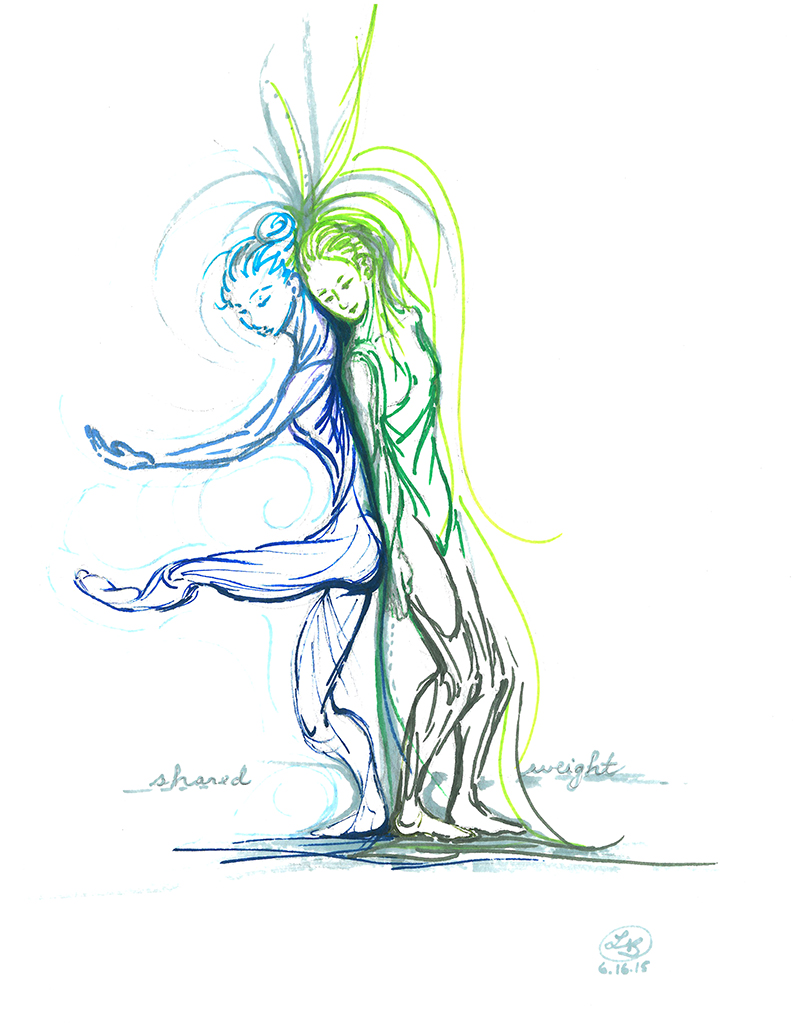

BY SOPHIA ROG; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT

This past spring, my friend Emmaly and I rented a little studio in Santa Fe on Thursday afternoons. The studio’s previous purpose was a two-car garage… so, it’s tiny, and not all that toasty in the early spring until the heater has been on for a good half of our two-hour sessions. This was the perfect space for our endeavor: to do a teaching exchange — my contact improvisation (CI) and Emmaly’s ballet. We’d dabbled in each other’s forms; I went to the University of Minnesota for two semesters and took ballet, while Emmaly danced in the Bay Area where CI-like movement principles infiltrate many of the classes and performances. Yet, we each knew we didn’t have a real understanding of the respective forms.

When I was accepted to the dance program at U of M, though I didn’t have one ballet class in my background I was placed in the intermediate class. I floundered in ballet, frustrated at the lack of value paid to anatomical understanding, at the lip-service given to imagery and somatic modalities (the teacher referencing “head tail connection” while demonstrating otherwise and unable to elaborate on what exactly that was), and the speed with which we went through exercises that should have been highly exacting. I just — didn’t get it. Conversely, Emmaly spoke of being in classes or rehearsal settings where it was often assumed the dancers had an understanding of CI principles, and feeling at best like she was faking it and at worst she was physically unsafe.

Respectively, Emmaly and I are both passionate about our forms. We can geek out excitedly about intricacies of movement, theory and history of these two very different dances. So we began. An hour of ballet, an hour of CI. Next week, an hour of CI, and hour of ballet and so on. We delighted in noticing some parallels; both forms are a very clear representation of the social climate in which they were created, and both make very complex movement pathways look easy and graceful. As a beginner in either form, it can be challenging to feel like one is actually dancing rather than awkwardly bending and straightening one’s knees, or rolling about on the floor.

Teaching CI to someone with a very developed physical awareness and dance patterning was fascinating, and in some ways was more challenging than teaching beginners who don’t have a dance background. I was hyper-aware of CI’s extreme physical intimacy and vulnerability in a way I haven’t been in years. What if I didn’t properly embody what I was teaching and she noticed? And, is Emmaly comfortable with this level of physical touch? Is she feeling awkward or unsafe? Then, because Emmaly could fairly easily achieve the physicality of the CI exercises I presented, it became necessary to attempt to express the ineffability of CI.

I began to realize what I really wanted to share with her was the “state of mind” (mind which includes body) that keeps me coming back to the form, fascinated and delighted. In CI, I’m carefully choosing my actions and, at the same time, abandoning my willfulness. I’m practicing skills and, at the same time, I have nothing to accomplish and no goal in mind. I’m engaging my muscles with only as much tone as is necessary for each current instant. I can flow through a wide range of tones swiftly, and I’m ready at any moment to be fully engaged or fully released. I employ a truly compassionate, generous, openness to my partner, yet am fully ready and willing to leave any dance that does not feel safe. I trust my partner enough to release to them my full weight, yet I retain complete responsibility for my own body.

Sometimes I became disgruntled with how amorphous CI is compared to ballet. I mostly left with more questions that answers. Taking ballet from someone willing to field even the most minutely detailed of questions was a delight. I began to understand ballet a little better in my body from the inside out — and what I mainly found is that it takes even more engagement of muscle than I realized. Emmaly emphasized that to her, ballet is about the specific intention and energy one puts into each movement, rather than about achieving a certain shape. She would tell me, “You’re already doing it” even when I had fairly butchered the combination — both the step and the sequencing — because she had seen that I was fully and totally engaged in trying. Which I made note of mentally, thinking, “Fascinating… ‘trying’ is definitely not the first word that comes to mind in terms of learning CI. There’s really something of not trying, of noticing where there is ease and going toward that. Yet, CI is certainly just as much based in a mind-body state and in intention as it is in achievement of any particular physical skill.”

A final parallel we commiserated on is how both ballet and CI tend to have a certain stigma within the dance world, and even in the wider community. Ballet is often pegged as being innately harmful to the body, rigid, out-of-date, narrow-minded, or overly harsh. CI is often seen as being a skill-less, touchy-feely, “just do what you feel” type of mush-pile on the floor. Bringing these two dances together in our little duet of sharing and learning was rich and satisfying; we got to express our love and opinions — our personal manifestos, if you will — about the dance forms we love so much, and bridge two worlds that could easily seem disparate.