Sebastian Grubb’s Story

BY LIZ BRENT

This interview is part of an ongoing series, Men Who Dance, which looks at the experiences of men in the field of dance.

Sebastian Grubb: I’m 30 and I’m considered a full-time dancer. I dance about 20 hours a week on average for pay with AXIS Dance Company. I do a little of my own choreography and also teach dance.

Liz Brent: How old were you when you started dancing?

SG: I started dancing when I was five but quit after two weeks because of being teased in ballet class. There were two boys and we both quit. I did musical theater from age four to 18. When I was 16 there was a dance company at my school that I got excited about. I took a variety of dance classes in college but there wasn’t a dance degree. It was a small school though so I could choreograph every semester. I choreographed for seven semesters and performed in two shows a year even though I wasn’t a dance major or minor.

LB: What are your earliest memories of dance?

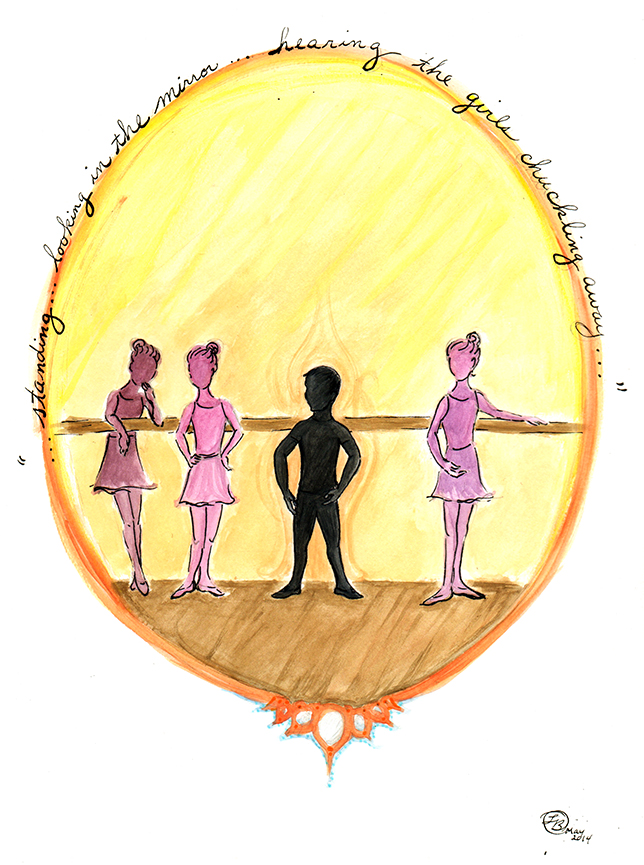

SG: In the ballet studio I remember doing an interpretive dance about a guy who has all these hats and then some monkeys steal the hats and take them up a tree. This was in Santa Cruz – it’s one of my earliest dance memories. Another is standing and looking in the mirror and hearing the girls chuckling away. They weren’t malicious intentionally, but they were unaccustomed to having a boy in class wearing tights.

I went back to that same studio when I was 20 for a one-month intensive. At that point I was a bearded 20-year-old with all these pre-pointe tweens. I was the only guy and maybe the least skilled person, but at least I had more confidence with myself at that point.

LB: What was your family’s reaction to you being involved in dance?

SG: I’ve had nothing but support. I had a mom who really encouraged me to pursue it and a dad who was just happy I was doing something artistic.

I always had this fear around dance that I had to convince men in my life that it was hard work, especially when I started working as a trainer. I had friends who were fitness freaks and I felt like maybe they thought dance wasn’t challenging and I had to somehow prove it required muscular effort, like a sport.

LB: Do you still feel that way?

SG: Less and less. I think there’s been a huge impact from popular dance television shows. More people are talking about dance and are interested in it. Those shows also emphasize how demanding it is, so when I tell people I’m a dancer the reaction is often, “Oh that’s really hard!”

LB: When was the moment when you decided dance was a career pursuit?

SG: The moment when I decided to try to pursue dance was when I was 19 and I went to a festival in Seattle with all men dancers and almost all men choreographers. It’s called Against the Grain – Men in Dance. It’s this great festival that happens every two years. Up until that point dance had been a hobby that I couldn’t imagine building a life around. At the festival I saw the huge variety of men who have chosen to pursue dance. It really opened my eyes and I decided to give dance a try.

And then I met Frey Faust, the originator of the Axis Syllabus – a biomechanics-based movement system and way to analyze movement for safety and efficiency. He is such an amazing dancer himself. He gave me a concrete foundation to build on out of college.

LB: Was there anyone when you were younger who was a role model?

SG: In high school there were boys who were better dancers than me. I’ve always thought that people who were better than me at something seemed like magicians of a kind, especially in dance, because I never fathomed how I could do certain moves. I’m thinking specifically of really advanced break dancers or ballet dancers. But it was always discouraging: how could I possibly catch up on the decade of training I had missed? They weren’t really role models. I don’t think I had a dance role model until Frey and then shortly after Scott Wells. Here in the Bay Area though there are several role models and dancers whom I aspire to emulate.

LB: Have you run into negative stereotypes?

SG: I’ve had guys my age make comments like, “Oh he’s gonna turn gay.” San Francisco already has a large gay population and then a large number of male dancers identify as gay. So there’s definitely that association.

I’m quite muscular, and partly it acts as body armor. I defend myself from negative points of view. I think it’s been partly conscious and partly unconscious, but it makes it harder for people to question what I do. They see I’m a strong fit person.

LB: What is your experience taking class? Are you often the only guy? What’s your response to that environment?

SG: I’m used to being one of the only men. It’s also true in musical theater that there’s more women than men. Going from theater to dance was not a big cultural shift.

I think it’s important for younger men in dance and theater to have a male role model or mentor to show them what they could aim for. If there’s a female teacher and a class of female dancers, a male dancer might wonder about his identity in the mix.

At this point it doesn’t bother me at all though. I feel extremely confident in myself as a dancer with a masculine identity, so it’s not an issue. But earlier it definitely was.

LB: Have you noticed a difference in attitudes toward male dancers in communities outside of San Francisco?

SG: Most of AXIS’ touring is to colleges and universities, though we also do outreach in rehab centers and sometimes go to a big presenter venue. I think if I spent more time going to bars and grocery stores and tried to engage people in different parts of the country, then I would have more challenging interactions. But I don’t necessarily look like a dancer, which is a marker. And aside from not identifying as gay, I don’t get people trying to categorize me.

LB: Is there anything specific you’ve learned from being a guy who dances?

SG: I think there’s a super interesting thing about being a man in dance in terms of getting work, which is really significant. It’s important to recognize that but also not let it devalue my capacity. I don’t want to think, “Oh I’m just getting work because I’m a guy.” That is a really disempowering perspective to have. It’s definitely an advantage though because something like ten percent of dancers are guys, but male dancers shouldn’t rely on that statistic. I think some men get work and then stop training. And then they’re not doing the work of a professional any more, or working at the level of prowess of many women in the field who don’t have professional work. Male dancers should be striving for excellence and that’s part of the response to the sex card is to say, “That’s true and I’m still working hard,” as opposed to being stoked for getting paid and then being a mediocre dancer.

LB: If you were to mentor a young male dancer, what would you pass on?

SG: In some ways the great thing about mentoring a young male dancer is, “You have a chance!” Whereas mentoring a young female dancer I’d know there’s a much smaller chance of them making it professionally. But with a male dancer, I’d ask, “Do you want to be you or be a mold of other successful male dancers?” You can get dance work and be hired because you fit a certain mold. Or do you want to be your own mold? Or be an innovative choreographer? Or just do beautiful dancing, because that’s a fine pursuit too. But dancers need to be clear on what’s going to be fulfilling. I’m challenged by the deluge of beautiful dancing because there’s not enough resources to support all the people who want to make pretty dances. But there are some interesting resources available for people who want to do something different with dance, who want to look at it as a larger art form in a bigger context.

I guess I don’t really have gender specific advice. Both sexes should also cross train and focus on being a fit artist. I really think of myself as a dancer-athlete, which creates some pretty cool opportunities choreographically and career-wise.

LB: Any other thoughts?

SG: This is true for any dancer, but particularly young dancers: I would recommend studying theater. Theater gives you presence and diversifies the ways in which you can be present through focus or facial expression or body posturing. I think it gives dancers a much better chance of getting hired for work.

Dance is so choreographer and director specific. That’s gotta be one of the biggest factors in deciding what to pursue. Who do you want to be working with? Even if the dancing is great, if the director is a pain in the ass to work with you’re not going to enjoy it for the most part. I’ve worked with a large number of choreographers, and it informs you. When I had my show “Work Out” a couple years ago, I knew what kind of relationship I wanted to have with the dancers to try to give them the best possible experience, and it was a very successful show in a few regards, and that’s one of them, that the dancers felt supported. I think it’s important when you’re training to look at other choreographers and dancers and find how you want to be, because in the end dance is such a social art form. It’s social and personal, because our bodies are on the line. I aim toward the care-taking side; let’s take care of one another.

Sebastian is a professional contemporary dancer, choreographer and teacher, and runs Sebastian’s Functional Fitness, an outdoor fitness program based in San Francisco. Learn more at www.sebastiangrubb.com. .

One Response to “Sebastian Grubb’s Story”

Sebastian’s website is linked incorrectly at the bottom of the article! It should be http://www.sebastiangrubb.com. Great interview!

Comments are closed.