Jeremy Smith’s Story

BY LIZ BRENT

This interview is part of an ongoing series, Men Who Dance, which looks at the experiences of men in the field of dance.

Jeremy Smith: I’m 31 and I’m a dancer with ODC Dance in San Francisco. I started dancing when I was nine. It was December or January of 92’ – 93’, and my family moved from Tampa, FL to just outside the Twin Cities in Minnesota. In an attempt to find activities for my sister and I to do during the holiday interim while we changed schools, my mom enrolled us in dance. The other options were hockey and such but I wasn’t very athletic and wasn’t interested in doing sports. I had always liked dancing around in the living room but had never wanted to go somewhere and learn, so I started because my mom kind of threw me in. The way my mom tells the story is she was waiting in the lobby of this rinky-dink dance studio in a shopping center and the teacher came running out asking, “Who’s the parent of the boy?” My mom was mortified and asked what had happened. The teacher said, “He’s got to stay. We really like him.”

Liz Brent: What are your first memories of dance?

Liz Brent: What are your first memories of dance?

JS: I remember learning how to do “Squish the Bug” where you poke an invisible bug with your foot in a circle. That’s my first strong memory. That first studio was a big competition studio, so I eventually got thrown into jazz, tap, lyrical and musical theater. Then we moved back to Florida and I started at another studio, and started going to a middle school with a dance program as well. It wasn’t an arts school but there was an arts component. And then I went to a performing arts high school. I can’t remember when I started ballet. It must have been once I entered middle school.

LB: What was your family’s reaction?

JS: They were always supportive. There was never confusion or problems with it. It was a good thing because it gave me something to do that had a social component. I grew up shy and am fairly introverted. I wasn’t good with teen sports. Dance was something that was both an individual pursuit and a bonding experience with the other dancers. My parents enjoyed going to shows and being a part of the culture.

LB: Did you go to college for dance?

JS: I went Florida State University in Tallahassee. I was able to complete my degree in three years. It was a great program that I liked and got a lot out of.

LB: Were you the only guy in your dance classes growing up?

JS: It was always very small numbers. I think there were times that I was, but once I got to high school there were a lot more, like ten to fifteen. Before that it was usually me and one other boy at most. At first I was too young to recognize any gender differences in that way. But for me there was a certain relief to it, because it was harder for me to relate to other boys. That goes back to it being a positive social experience for me. It was harder in middle school in Miami though than it was in Minnesota. I remember one incident in particular. In the boys’ locker room the other boys would change for athletics or P.E. whereas I would change for dance class. And I remember finding my clothes were taken and spit on. How the incident got resolved is kind of a blur. I remember the school let me change in a closet in the studio instead so I wouldn’t have to go into that negative environment. That was a big turning point in my realization that dance was something that was not necessarily acceptable in the culture in which I was living. It wasn’t normative; boys don’t dance, girls do.

LB: How did it shift in high school and college?

JS: High school was better because I was in an environment where everybody was doing arts. It was the culture. And college was the same. Of course I interacted with people who weren’t in my program but I was older too and knew how to handle things better and socially navigate and be more confident. It takes confidence to allow yourself to be okay doing what you’re doing.

LB: What’s your professional trajectory been?

JS: My career really began with Parsons Dance in New York, which I auditioned for my last year of college. David Parsons wanted to hire me but knew I had a few months of college left so he let me finish and then brought me on as an apprentice. Shortly after that he hired me and I danced there for three and a half years. At the same time I danced for Ben Munisteri and Lydia Johnson. And then I took the job with ODC and I’ve been here seven years.

LB: Have you run into any stereotypes particular to male dancers?

JS: Yeah. Most people think all male dancers must be gay, or there must be some sort of extra femininity. The other stereotype is that men have it easier than women, that it’s easier for men to get jobs than it is for women. Those are the two prevailing stereotypes that exist. Both have truth to them, but are very troubling as well. One implies a sexuality that may not be true, and the other implies we didn’t have to work to have gotten where we are.

The one I find more troubling is that men have it easier than women, because I know how hard I have worked. But then I’ve also been very lucky. I’ve gotten a job that I wanted with very little rejection in my career. So I have been very fortunate, but that’s not true for everybody. When I worked for Parsons, auditions had hundreds of people, and it’s not any easier for those boys than it is for those girls.

LB: Do you feel like awareness around these stereotypes has changed?

JS: I do to a certain degree. There’s a bigger media presence in dance. It’s on tons of TV programs and YouTube. I think it backfires though because it facilitates some of those stereotypes. I think the idea of men dancing is still linked to sexuality. The stereotype is that men who dance are homosexual. I’d say in fact it’s about 50-50. A large portion of male dancers are homosexual because it’s a culture in which gay youth can usually grow up very safely. So that stereotype does prevail. But there’s also 50 percent that are heterosexual men. But I think there’s a whole culture of heterosexual male dancers that breed problems in terms of sexual stereotyping for their homosexual counterparts. In my experience there’s a big difference in perspective and confidence between the gay men who dance and the heterosexual men who dance, and the heterosexual men who dance tend to be much more confident and much more assured and tend to have much larger egos. Heterosexual men can combat all those stereotypes very easily. When you’re younger and you’re actually gay you’re not in a place where you have the defense to say anything against those stereotypes yet, so it’s much more difficult. Those barriers have to be overcome.

LB: How do different communities stereotype male dancers differently?

JS: I think a lot of the stereotypes we’re speaking of exist in this country in particular because we have bigger sexuality issues that get embedded in career identities.

If you look at the performing arts historically, the men always dominated. Think of Shakespeare where the men always played the women’s parts. Now of course that has issues as well. But for example there is a large male dance culture in ethnic dance forms. In our culture there’s a much bigger disconnect and a lot of it is social and cultural and how that then gets attached to ballet and concert dance.

LB: Any last thoughts?

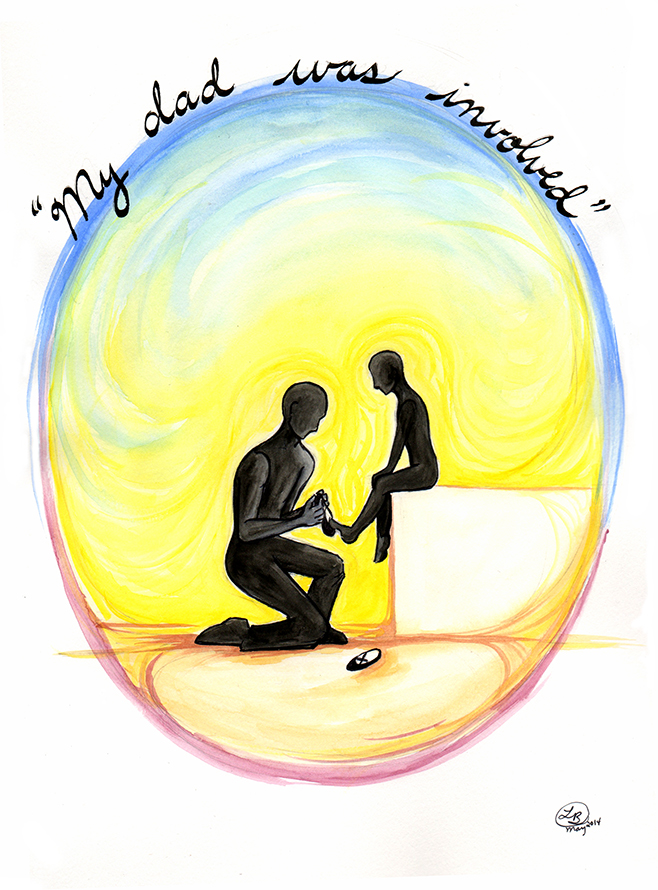

JS: Looking back, I really appreciate my dad, because I think that’s a big piece of the trouble puzzle for boys dancing is that the fathers can be quite unsupportive and just not understand. It becomes about other beliefs rather than it being just an activity. I really appreciate how much my dad never once questioned it and when I was little he even helped me change and get my costume on and get ready. My dancing wasn’t an issue in our relationship.

Dance often ends up being a mom culture. Think of that TV show Dance Moms, for example. And that might be part of the cultural problem too, that dance is not a way for fathers to bond with sons.